Health care provider recommendations key to H1N1 vaccination

Health care provider recommendations key to H1N1 vaccination

Following the first outbreak of H1N1 influenza in April 2009, the US government established a plan to deal with a possible pandemic. The government purchased large quantities of a new H1N1 vaccine and made recommendations about who should receive it. Funds were provided to make H1N1 vaccine available not only in doctor’s offices but also through schools, public health clinics, and retail settings.

The first doses of H1N1 vaccine became available in late September 2009. The amount of vaccine was limited initially, but vaccine became more widely available in the following months.

With vaccination as the key US response to the possible H1N1 pandemic, public willingness to accept H1N1 vaccine is a critical measure of success. To study H1N1 vaccine acceptance among the general population, the C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital National Poll on Children’s Health conducted a national survey in January 2010.

H1N1 Vaccination Rates

The poll found that 29% of children and 16% of adults have received H1N1 vaccine as of January 2010. Children with high-risk medical conditions (for example, asthma) were more likely to have been vaccinated (37%), as were adults with high-risk conditions (21%). Only 5% of those polled report they had tried but could not get the vaccine for themselves or their children.

Provider Recommendations for H1N1 Vaccination

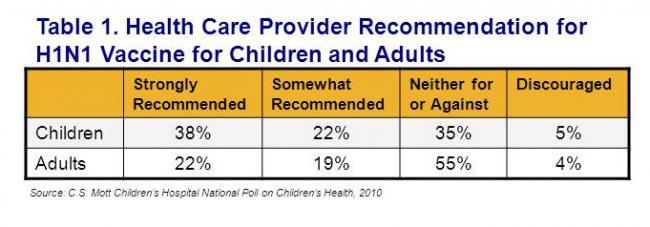

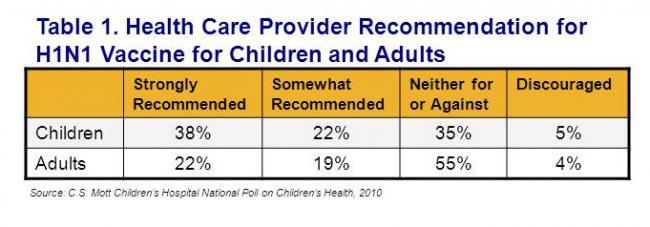

The public perceived mixed recommendations about H1N1 vaccine from their health care providers. Only 38% of parents reported that their children’s health care provider strongly recommended H1N1 vaccine. Only 22% of adults reported that their own health care provider strongly recommended the vaccine (Table 1).

Health care provider recommendations for H1N1 vaccine were strongly related to receipt of the vaccine among children and adults. Two-thirds of children, and well over half of adults, whose providers strongly recommended the H1N1 vaccine were vaccinated (Figure 1). H1N1 vaccination rates for children and adults were considerably lower if their health care providers did not strongly recommended the vaccine.

Importantly, health care providers were much more likely to strongly recommend H1N1 vaccine for children and adults with high-risk conditions. This translated into higher H1N1 vaccination levels among high-risk groups.

H1N1 Flu Vaccination Sites

Poll results demonstrate that the efforts to expand the availability of H1N1 vaccine in different settings were successful. While a doctor’s office was still the most common vaccine site for both children and adults, more than one-quarter of children were vaccinated at school clinics, while pharmacies, retail clinics and workplace clinics accounted for 1 in 5 adult H1N1 vaccinations (Figure 2).

Future Plans for H1N1 Vaccination

Highlights

- Receipt of H1N1 vaccine closely tied to having a health care provider strongly recommend the vaccine.

- Only 2 in 5 parents reported that their children’s providers strongly recommended H1N1 vaccine; only 1 in 5 adults reported that their own providers strongly recommended H1N1 vaccine.

- Only 1 in 10 of those not yet vaccinated intend to get the H1N1 vaccine; another 25% would get vaccinated if the H1N1 outbreak worsens.

- Providers were more likely to recommend H1N1 vaccine for children and adults at high risk for complications of influenza.

Implications

Results of this poll emphasize the critical role of health care providers in helping their patients make decisions about new vaccines: a strong recommendation about H1N1 vaccine from a health care provider heavily influenced whether an individual child or adult was vaccinated. Unfortunately, information on H1N1 vaccine safety and effectiveness—key data on which providers could base recommendations—was not available until September 2009. Additional data about H1N1 illness and H1N1 vaccine came in over the following months. Many health care providers may have had less information than usual about this vaccine, just because of the timing of the pandemic and vaccine production. As a result, many providers may not have felt comfortable making strong recommendations in favor of the H1N1 vaccine, even if they typically recommend seasonal flu vaccine and other approved immunizations.

Even in this context of limited data about the vaccine, health care providers likely were aware of epidemiologic data that H1N1 disease had a disproportionately severe effect on children. Providers may have based their recommendation for vaccination of children on that increased risk of disease. Poll results support this hypothesis, with respondents reporting a much higher proportion of health care providers giving a “strong recommendation” for children than for adults. In fact, for adults the public perceived that the majority of health care providers did not recommend for or against the vaccine. Of note, health care providers were more likely to strongly recommend the H1N1 vaccine for high-risk patients than those without high-risk conditions, again suggesting that the risk of disease may have outweighed the lack of data about the vaccine. Importantly, only a small number of poll respondents indicated that health care providers recommended against H1N1 vaccine, for either children or adults.

Looking ahead to the 2010-11 influenza season, public health officials should emphasize the dissemination of vaccine safety and effectiveness data to health care providers, so that they are in a position to make recommendations to their adult and child patients. This may be key to increasing H1N1 vaccination coverage above current levels.

These poll results also indicate that after initial periods of limited supply, H1N1 flu vaccine availability caught up with public demand. Only 5% of respondents in this poll indicated that they had been unsuccessful in obtaining H1N1 flu vaccine. Moreover, these poll results demonstrate the positive outcomes of efforts to make H1N1 flu vaccine available in a variety of settings: substantial numbers of children were vaccinated in school settings, and many adults were vaccinated in workplace or retail locations.

Data Source & Methods

This report presents findings from a nationally representative household survey conducted exclusively by Knowledge Networks, Inc, for C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital via a method used in many published studies. The survey was administered in January 1-18, 2010 to a randomly selected, stratified group of adults aged 18 and older (n=2,246) from the Knowledge Networks standing panel that closely resembles the U.S. population. The sample was subsequently weighted to reflect population figures from the Census Bureau. The survey completion rate was 75% among panel members contacted to participate. The margin of sampling error is plus or minus 2 to 4 percentage points for the main analysis. For results based on subgroups, the margin of error is higher.

This Report includes research findings from the C.S. Mott Children's Hospital National Poll on Children's Health, which do not represent the opinions of the investigators or the opinions of the University of Michigan.

Citation

Davis MM, Singer DC, Butchart AT, Clark SJ. Health care provider recommendations key to H1N1 vaccination. C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital National Poll on Children’s Health, University of Michigan. Vol 9, Issue 1, January 2010. Available at: http://mottpoll.org/reports-surveys/health-care-provider-recommendations-key-h1n1-vaccination.